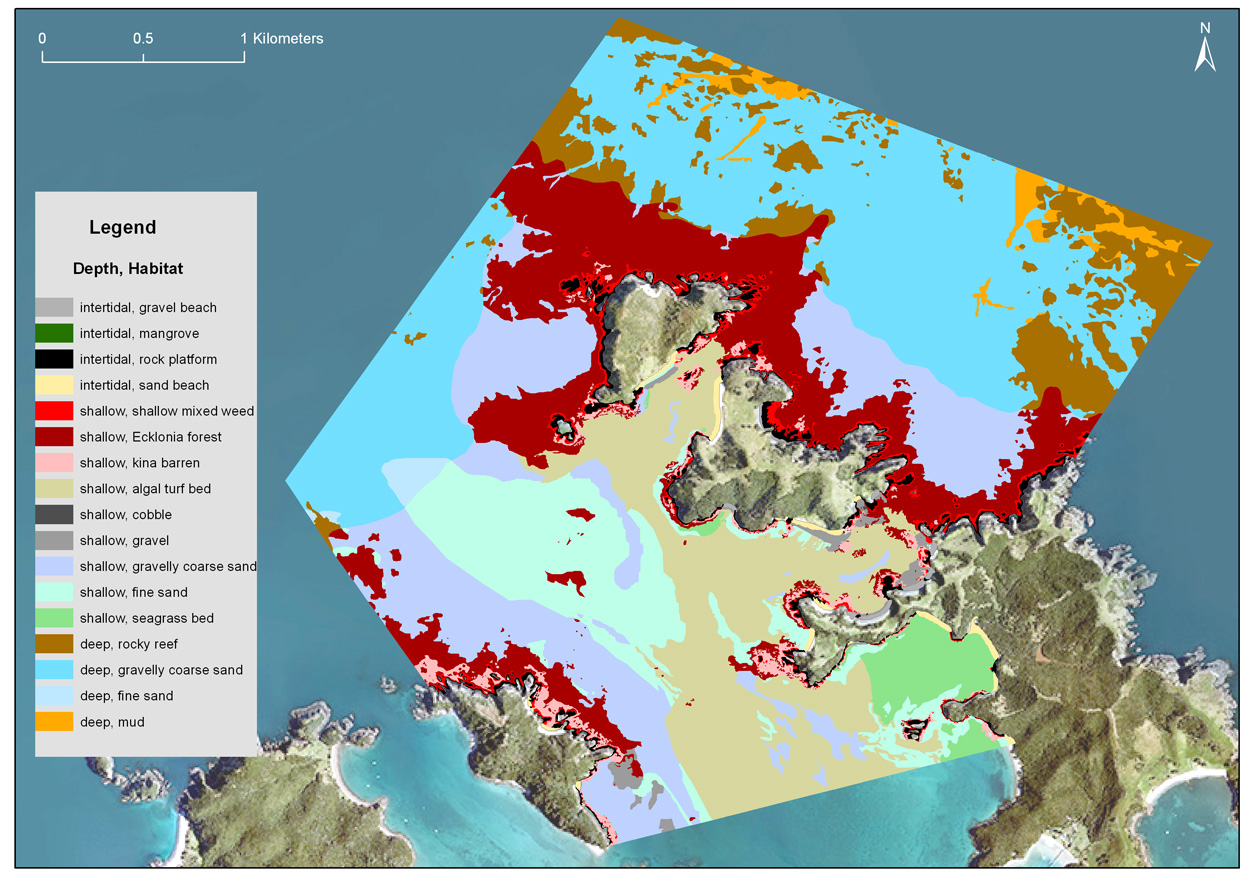

Mimiwhangata Habitats poster (Kerr & Grace 2005)

Mimiwhangata Habitats poster (Kerr & Grace 2005)

This crucial area of marine conservation attracts much debate and unfortunately sometimes uninformed opinion from people opposing marine reserves. It is important to review some of the extensive literature on this subject and to summarise the principles of design for yourself. This will enable you to clearly explain to anyone what things are being considered in the design of your marine reserve. We urge your group to be clear in your own minds what the goal is for your design project. To formulate your goal in practical terms, it may help to review the various sources referred to in this section on the principles of marine reserves. Checking your goal against IUCN CBD Technical Series #13 is also a good idea. Experience has shown both here in New Zealand and overseas when design groups fail to reach an understanding of the goal for what the size and extent of the reserve or reserves should be, results often disappoint. Frequently in the absence of an agreed goal, other agendas take over the process.

We have put together an archive of selected scientific works looking at various aspects of Marine Reserve Design. In the Library, there are also three other archive folders which have marine research reports: Marine Science and Research, Marine Habitat Mapping and the works Dr Bill Ballantine. Our first marine subtidal habitat map, Mimiwhangata, (Ballantine, Grace & Doak 1974)All are relevant to understanding marine reserves. All this information is relevant to the development of proposals and formal applications for marine reserves under the Marine Reserves Act, however, this information is also the background required to prepare or consider proposals in a marine protection forum process as well.

Our first marine subtidal habitat map, Mimiwhangata, (Ballantine, Grace & Doak 1974)All are relevant to understanding marine reserves. All this information is relevant to the development of proposals and formal applications for marine reserves under the Marine Reserves Act, however, this information is also the background required to prepare or consider proposals in a marine protection forum process as well.

Principle-based or species and ecological details based?

On one hand, it could be argued that some very basic principles are all that is required. There are so few marine reserves at present that in most localities any marine reserve design will protect habitats and marine communities that are unlikely to be protected anywhere else. In other words, for these first marine reserves, it is hard to put them in the 'wrong' place.

The real message and central argument here is that it makes sense to have some part of each coast protected, left as natural as possible. From here you can keep building your argument and understanding. There are, of course, all the social and cultural considerations that enter into the equation and quite often become the main focus of debate or opposition.

On the other hand, the science of how marine reserves work ecologically and how they can be sited has unlimited complexity, because ocean systems are so vast, so interconnected and so poorly described in comparison to land systems. Work in this area has been underway for the last several decades, and in the last decade especially there has been an explosion of scientific work on reserve design. Most international work is now focused on applying what has been learned about individual marine reserves and marine ecology to understanding the properties and design of systems or networks of marine reserves.

It is wise to enlist help from a marine biologist to help you through this part of the process, but failing this you can proceed based on an understanding of the basic principles. The various papers on marine reserve design principles by Dr Bill Ballantine lead this discussion both here and internationally. Bill's work is clear sensible, practical and there is a strong argument that we could design effective networks of marine reserve based purely on these principles. However, there are now many other aspects that of design that has been explored in the literature.

Motukaroro habitats map Whangarei Harbor Marine Reserve (Kerr 2008)We suggest is worthwhile keeping design questions in mind when you are looking through the various case studies and marine reserve applications and proposals. As often happens during design, social considerations come into play, such as ease of public access or factors to do with who owns the adjoining coastal land. You will discover when you study the past proposals and applications that there are many different ways people have justified the design of their marine reserve. This will be valuable when planning how you approach the design challenge.

Motukaroro habitats map Whangarei Harbor Marine Reserve (Kerr 2008)We suggest is worthwhile keeping design questions in mind when you are looking through the various case studies and marine reserve applications and proposals. As often happens during design, social considerations come into play, such as ease of public access or factors to do with who owns the adjoining coastal land. You will discover when you study the past proposals and applications that there are many different ways people have justified the design of their marine reserve. This will be valuable when planning how you approach the design challenge.

Practical and Functional Boundaries

As your process develops and actual designs are emerging, it is vital to be practical about boundaries. Do they make sense in terms of compliance and marking of boundaries? Consider such things as navigation and how markers could be seen from people on the water, and do the boundaries make sense ecologically.

We recommend you check your design work against the Marine Reserve practical guideline advice paper by Vince Kerr.

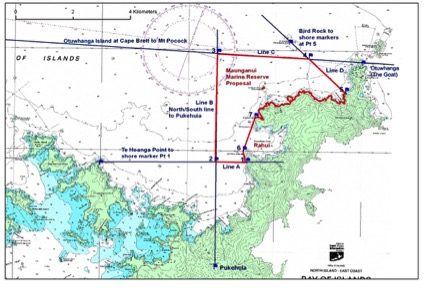

Cape Brett boundary analysis example (Kerr 2014)

Cape Brett boundary analysis example (Kerr 2014)

We suggest that you study the two examples below of boundary assessment of marine reserve proposals. They both support reports on marine reserve proposals. Reports like these serve as an important step in achieving the best possible boundaries for each situation. They are also valuable support documents for the approval of a marine reserve. This is because in the final stages DoC is tasked with thoroughly evaluating the boundary selection before a marine reserve can be approved.

Boundary Assessment Report Examples: (it may be helpful to refer to the proposal documents associated with these two reports found in Applications and Proposals archive)

Fish Forever Bay of Island Marine Reserve Proposal Boundary Assessment

Mimiwhangata Marine Reserve Proposal Boundary Assessment

The Importance and Use of Habitat Maps

Marine Habitat maps have featured in many of the marine reserve projects in New Zealand. They are a common feature in many of the international best practice models. Always with marine work, the big challenge is to find ways of describing what's out there, beyond a blue horizon. Under the surface, we know marine ecosystems are very complex and are very much influenced by depth, topography substrate, currents and up-dwellings. These major physical environmental factors can usually be mapped, if not with existing information, then to a useful level with basic survey equipment and effort.

Ideally in all cases when we sit down to plan for marine protection we would have the perfect biological knowledge, know what lives where, how their life cycles work, how their larval dispersal works, home territories, ecological connections etc. In practice, we can't put all this information together as it is just too challenging a job. What's the solution? We have already emphasised that the start point is to work with the principles that have been best described by Bill Ballantine. Bill demonstrated in his writings and teachings that in fact, you can design an effective marine reserve network with only basic information on currents, bathymetry and readily accessible knowledge of the local coast. Taking this a step further Bill along with help from colleagues suggested that we should attempt marine habitat mapping with simple tools, using a variety of scales that best tell the story of the habitats and communities we are most interested in or are most representative or ecologically meaningful to the area of interest. He stressed that habitat maps of this type should have a combination of the major physical habitats that drive ecosystems combined with the major biological communities which define the area, such as a shallow kelp forest in Northern New Zealand. He stated that each map should not contain more than about 20 classifications, in order to remain clear in terms of boundaries and interpretation.

The first map of this form in New Zealand was brought together by Bill, Roger Grace and Wade Doak in the early 1970's at Mimiwhangata in Northland. Following this, similar projects and maps were made for the Leigh Marine reserve and Mokohinau Islands by teams of students and volunteers led by Bill Ballantine, Dr's Bob Creese and Tony Ayling and others from Auckland University's Leigh Lab.

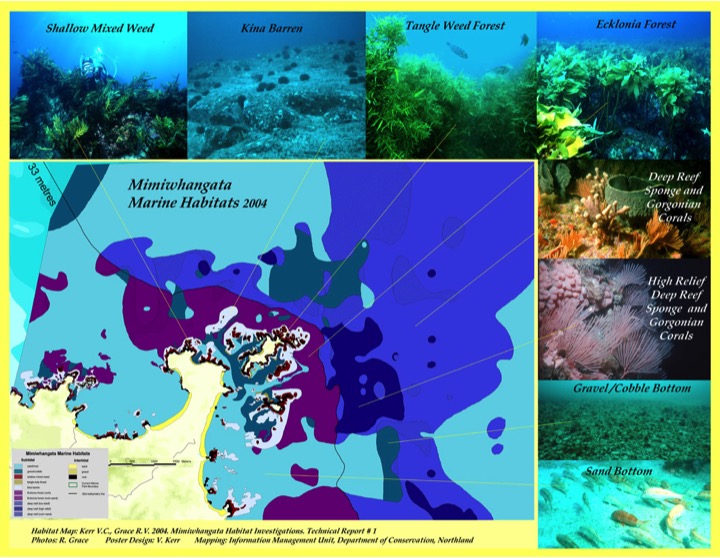

In 2005 a second marine habitat map of Mimiwhangata in Northland was completed by the Roger Grace/Vince Kerr team. This work was modelled on the original approach pioneered by Bill Ballantine in the 70's. For this second map, better information and tools were available and the area studied was enlarged to include the deeper habitats off Mimiwhangata. This habitat map proved invaluable as a planning tool. It also helped to engage the community with the ecology of Mimiwhangata, the issues around biodiversity, understanding the need for a marine reserve, and the sorts of benefits that could be expected from establishing a marine reserve. The 2005 habitat map report for Mimiwhangata has a methodology section explaining how the work was done and detail descriptions of the habitats shown in the poster below.

A poster of the 2005 Mimiwhangata Habitat Map with illustrations of the major habitats mapped

The Marlborough Regional Council has invested in seafloor habitat mapping to support their work with identifying significant ecological areas. They have a Seabed Mapping web page that provides access to their reports and maps.

Go to the Marine Habitat Mapping Archive section of the Library to see a range of examples of work completed in New Zealand.

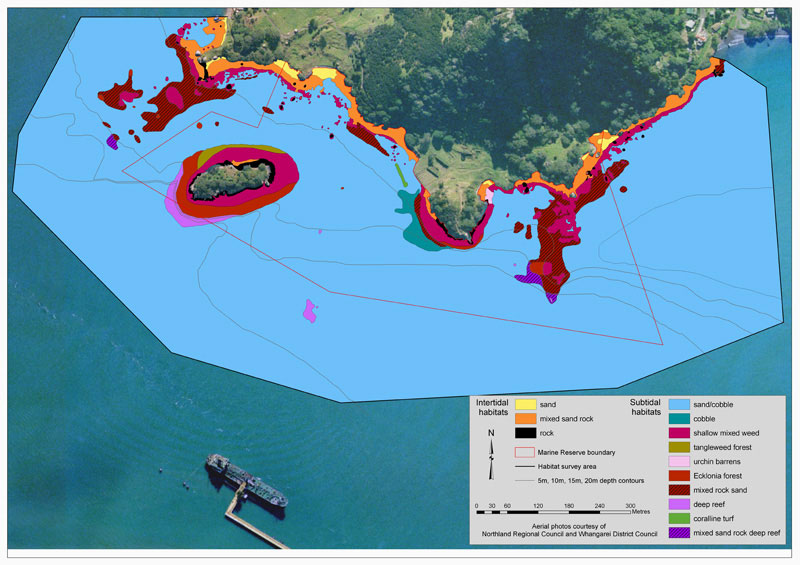

Waewaetorea Island, Bay of Islands Habitats (Kerr & Grace 2015)

Waewaetorea Island, Bay of Islands Habitats (Kerr & Grace 2015)