Northland students celebrate the opening of Whangarei Harbour Marine ReserveMarine conservation in NZ has a fascinating history starting with arrival of early Māori with holistic tikanga based lore. With arrival of more people came greater pressure on the marine environment. Today, we live in a complex legislative system where biodiversity value is considered against fisheries management and economic drivers. Such as in the Resource Management Act, Coastal Management Policy, Fisheries Act and Conservation Act. NZ has been a global leader in conservation with the world's first national park at Mount Tongariro, established in 1894.

Northland students celebrate the opening of Whangarei Harbour Marine ReserveMarine conservation in NZ has a fascinating history starting with arrival of early Māori with holistic tikanga based lore. With arrival of more people came greater pressure on the marine environment. Today, we live in a complex legislative system where biodiversity value is considered against fisheries management and economic drivers. Such as in the Resource Management Act, Coastal Management Policy, Fisheries Act and Conservation Act. NZ has been a global leader in conservation with the world's first national park at Mount Tongariro, established in 1894.

NZ also was one of the first countries to introduce biodiversity protection legislation in the sea with the Marine Reserves Act 1971. Yet, protection of our seas has seriously lagged behind terrestrial conservation. On land just over 32% of our land area is protected for conservation purposes (MfE, 2007). As of 2016, 9.5% of our territorial sea is protected in marine reserve status. But, 99.72% of this is found around the large offshore island marine reserves at the Kermadec and Auckland Islands leaving many marine ecosystems unprotected. Only 0.28% of mainland New Zealand, a total of 511 square kilometres out of 182,072 is fully protected. In our total EEZ (Economic Exclusive Zone) only 0.0042% is protected within a no take marine reserve. We clearly have a lot more to do..

Early Beginnings – Tikanga Based Lore

Marine conservation in NZ started with the first arrival of polynesian settlers. The culture that travelled to New Zealand from the Pacific was rich with management tools. As tangata whenua explored this land these tools were used in the management of all resources, which was based on the belief of whakapapa (genealogy) from the atua (gods) born of Ranginui (sky father) and Papatuanuku (earth mother). Tane was the god of the forests and birds from which people descended, and Tangaroa gave forth the life in the oceans. These atua were siblings and so, all life within the oceans is connected to the land. These connections were real in day to day lives through oral histories, waiata and korero.

The complex tikanga (societal lore) that traveled from the Pacific was adapted to the conditions found in Aotearoa (New Zealand). As villages and tribes grew, management was maintained at a local level by the hapū (subtribe) and whānau (families) that held mana (authority, jurisdiction) over the area. Management practiced by Māori was holistic, incorporating spiritual lore along with fisheries management. The responsibility of tangata whenua to enact kaitiakitanga (guardianship) was handed down from the atua, and ensured the mauri (life force) of living and non-living parts of the environment remained paramount.

Rāhui (temporary ban) is the best known example of traditional management where a ban may be placed for a number of reasons. Karakia (prayers) to invoke tapū and utu (revenge or justice) protected such rāhui in the past. Today rāhui is written into the Fisheries Act 1996.

Transition from Lore to Law

Arrival of early whalers followed by European settlers saw the arrival of more fishing technology and a slow transition from tikanga locally based management to what can be best described as "free for all". Exploitation of marine mammals such as seals and whales is characteristic of this period. A boom and bust oyster export industry popped up and disappeared in the 1880-1890's due to overexploitation. The first legislation to control fisheries in NZ waters was the Fish Protection Act 1877 setting mesh size regulations. Licensing of fishing vessels and catch limits were used over the years to manage the growing fishing industry, yet still resulted in a crisis point for NZ's most valuable finfish stocks in the 1980's. This resulted in the start of a quota management system (QMS) outlined in the Fisheries Act 1996 setting total allowable catch limits based on fisheries science, leaving ecosystem functions out of the equation.

Environmental Change - From Big Fish to Little Fish

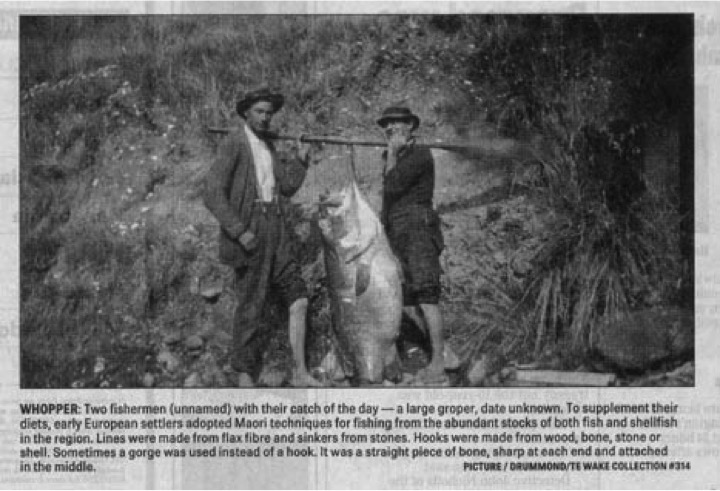

Hokianga around the turn of the century large Hapuku were caught on shallow reefsThose that lived through the 1900's saw huge change in their marine environment, not only in the abundance and size of their favourite food species. Through these decades fishing pressure increased and affected nearly all of New Zealand's coast. Land based effects were taking their toll on the ocean, with the loss of seagrass beds and health implications such as shellfish poisoning from sewage spills and heavy metal contamination in many of our harbours. Not enough research was being carried out on the effects of humans on the marine environment in NZ and internationally.

Hokianga around the turn of the century large Hapuku were caught on shallow reefsThose that lived through the 1900's saw huge change in their marine environment, not only in the abundance and size of their favourite food species. Through these decades fishing pressure increased and affected nearly all of New Zealand's coast. Land based effects were taking their toll on the ocean, with the loss of seagrass beds and health implications such as shellfish poisoning from sewage spills and heavy metal contamination in many of our harbours. Not enough research was being carried out on the effects of humans on the marine environment in NZ and internationally.

Beginnings of Modern Marine Conservation & Marine Science

The advent of SCUBA in the 1950's allowed greater exploration by scientists, and with more knowledge came more questions about the marine environment. It was a group of inquisitive marine biologists at Auckland University's Leigh Marine Laboratory that initiated legislation for marine reserves – no-take areas of the sea. It was difficult to convince communities, bureaucrats and politicians as there were not many examples available proving the benefits of marine reserves. With persistence of the likes of Professor Val Chapman and Bill Ballantine, and the support of Forest and Bird, NZ Underwater Association and NZ Marine Sciences Society, the first legislation of its kind was passed in 1971.

Understanding changes in marine biology was just the beginning, as unexpected outcomes included an increase in visitors to the area including SCUBA divers, photographers and schools. Commercial fishers were talking of more fish and crayfish being caught than before in areas around the reserve. Those who opposed the idea were now strong supporters of the marine reserve.

NZ Marine Conservation Today

Today there are many legislative tools that can be used for marine conservation including marine reserves, benthic protection areas, marine parks (by special legislation), rāhui (temporary closures), mātaitai and taiapure. With greater understanding of the diverse and complex needs of our marine environment came a greater acceptance for rule changes in the sea to prevent environmental degradation, such as biosecurity regulations and aquaculture restrictions. New Zealand adheres to many international agreements such as the UN Convention of the Sea to prevent the 'tragedy of the commons'. At a local level citizens are taking leadership in ensuring their local marine environment is protected.

A red moki at Motukaroro Island, Whangarei Harbor Marine ReserveGovernment leadership in marine protection in NZ is guided by the MPA Policy published in 2006 and the guidelines published in 2008 stating a 10% protection goal for coastal NZ. It outlined the standards for integrating marine reserves along with other legislative tools to protect biodiversity using a regional marine planning and protection forum process. Standards for scientific bases and regional consultation are defined in the policy. To date, this Department of Conservation & Ministry of Fisheries assisted forum process has been completed in Fiordland, Sub-Antarctic Islands, the West Coast and Kaikoura. While this policy guides government resources in creating marine protected areas, non government groups can work towards generating the information needed to prioritise marine reserves as the highest form of ecosystem protection available. In fact many of NZ's marine reserves are the outcome of non-government led processes, for example Kamo High School's Whangarei Marine Reser

A red moki at Motukaroro Island, Whangarei Harbor Marine ReserveGovernment leadership in marine protection in NZ is guided by the MPA Policy published in 2006 and the guidelines published in 2008 stating a 10% protection goal for coastal NZ. It outlined the standards for integrating marine reserves along with other legislative tools to protect biodiversity using a regional marine planning and protection forum process. Standards for scientific bases and regional consultation are defined in the policy. To date, this Department of Conservation & Ministry of Fisheries assisted forum process has been completed in Fiordland, Sub-Antarctic Islands, the West Coast and Kaikoura. While this policy guides government resources in creating marine protected areas, non government groups can work towards generating the information needed to prioritise marine reserves as the highest form of ecosystem protection available. In fact many of NZ's marine reserves are the outcome of non-government led processes, for example Kamo High School's Whangarei Marine Reser

Timeline of NZ Marine conservation, Science and Legislation Highlights

- 1947 - Jacques Cousteau's Aqualung goes on sale for the first time marking the beginning of widespread SCUBA use

- 1950 - Harbours Act

- 1953 - Wildlife Act

- 1964 - Continental Shelf Act

- 1965 - A nine nautical mile fishing zone was established outside the 3 nautical mile territorial zone

- 1971 - Marine Farming Act

- 1971 - Marine Reserves Act – providing the greatest protections for marine environments

- 1975 - Cape Rodney – Okakiri Point Marine Reserve (Goat Island) created (the marine reserve was not enforced until 1977)

- 1977 - Reserves Act

- 1977 - Tawharanui Marine Park created with no-take rules

- 1978 - 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) created

- 1978 - Marine Mammals Protection Act – allowing for marine mammal sanctuaries

- 1981 - NZ's second marine reserve established at the Poor Knights islands

- 1987 - Crown Minerals Act

- 1987 - Conservation Act

- 1990 - Kermadec Islands Marine Reserve approved

- 1991 - Resource Management Act

- 1991 - Driftnet Prohibition Act

- 1992 - Kapiti and Mayor Island Marine Reserves approved

- 1992 - Waitangi (Fisheries Claim) Settlement Act

- 1993 - Long Island Kokomohua, Te Awaatu, Piopiotahi, Te Whanga nui a Hei & Tonga Island Marine Reserves Approved

- 1993 - Biosecurity Act

- 1994 - Westhaven Marine Reserves approved for Golden Bay

- 1994 - International Whaling Commission creates the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary

- 1994 - Maritime Transport Act

- 1995 - 2 Auckland Region marine reserves approved at Long Bay Okura & Motu Manawa (Pollen Island)

- 1995 - Guardians of Fiordland formed to maintain or improve the quality of Fiordland's marine environment and fisheries

- 1996 - Submarine Cables and Pipelines Protection Act

- 1996 - Fisheries Act – allows marine parks, Mataitai reserves, , Taiapure, Section 186 temporary closures, Rahui, Benthic Protection areas and seamount closures

- 1997 - Te Angiangi Marine Reserve approved

- 1999 - Te Pohatu (Flea Bay) & Te Tapuae o Rongokako Marine Reserves approved

- 2000 - Biodiversity Strategy released

- 2003 - Te Matuku Bay Marine Reserve approved

- 2003 - Auckland Islands Marine Reserve approved

- 2003 - Guardians of Fiordland reccommendation report released

- 2004 - Ulva Island Te Wharawhara Marine Reserve approved

- 2004 - Maori Fisheries Act

- 2004 - Maori Commercial Aquaculture Claims Settlement Act

- 2004 - 33% of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (Australia) protected in no-take zones

- 2005 - Foreshore and Seabed Act

- 2005 - West Coast Marine Protection Forum formed

- 2005 - Fiordland (Te Moana o Atawhenua) Marine Management Act , including 8 new marine reserves approved

- 2005 - Guardians of Kaikoura formed

- 2006 - Whangarei Harbour Marine Reserve approved achieving a world first student created marine reserve thanks to the students and staff of Kamo High School

- 2006 - Parinihinihi, Horoirangi & Te Paepae o Aotea Marine Reserves approved

- 2006 - Marine Protection Areas Policy Statement & Implementation Plan released

- 2007 - Benthic Protection Area Accord signed closing 17 areas (1.2 million km2) to bottom trawling & dredging, also preventing any new MPA's from being created in NZ waters until 2013

- 2008 - Set net ban on ranging areas of Maui and Hector Dolphins

- 2008 - Tapuae & Taputeranga Marine Reserves approved

- 2008 - Marine Protected Areas Classification, Protection Standard and Implementation Guidelines released

- 2010 - West Coast Marine Protection Forum release their reccommendation report

- 2013 - Akaroa Marine Reserve approved after 17 years of consideration by 6 conservation ministers

- 2013 - West Coast Marine Reserves approved at Hautai, Kahurangi, Punakaiki, Tauparikākā and Waiau Glacier after an 8 year forum process

- 2013 - Hauraki Marine Forum Spatial Planning working group formed

- 2014 - Kaikoura Marine Management Act passed establishing 1 marine reserve and a number of other marine protection measures

Abundant fish numbers at the Leigh Marine ReserveAfter the first marine reserve became operational in 1977 at Goat Island, the ecosystem benefits of marine reserves became apparent. Over time, in places where bare rocky reef had been mainly inhabited by small kina (sea urchin) dense kelp forest regenerated within 8 years. Along with the kelp came more species dependent on the this kelp cover. The territorial behaviour of the male Spotted Wrasse and it's relevance in mating behaviour became understood, all because the inhabitants of the reserve were left to their business. In 2007 snapper were 30.2 times more abundant within than outside the reserve, and in 2009 lobster were 5 times more abundant than outside the reserve.

Abundant fish numbers at the Leigh Marine ReserveAfter the first marine reserve became operational in 1977 at Goat Island, the ecosystem benefits of marine reserves became apparent. Over time, in places where bare rocky reef had been mainly inhabited by small kina (sea urchin) dense kelp forest regenerated within 8 years. Along with the kelp came more species dependent on the this kelp cover. The territorial behaviour of the male Spotted Wrasse and it's relevance in mating behaviour became understood, all because the inhabitants of the reserve were left to their business. In 2007 snapper were 30.2 times more abundant within than outside the reserve, and in 2009 lobster were 5 times more abundant than outside the reserve.